Where do I find bash and how is it used?

We learned that bash is little more than a program on your computer waiting for you to start it and give it commands to perform. We learned that interacting with bash generally happens through a text-based interface where you "speak" by writing commands using the bash shell language and receive feedback in the form of textual output or the results of running other programs.

Before we dive right into the thick of it, let's first get our bearings. It's important that you understand where the bash program lives, how it's invoked, and what its environment is. How far does its reach extend and whom are its friends upon which it can call for help in performing the tasks you will instruct it to do.

Where do I find bash? How do I start using it?

Assuming that your operating system came with bash installed, you'll find bash as a simple executable program located in one of your system's standard binary directories. A binary is an executable program that contains "binary code" which is executed directly by the system's kernel. If you're running a system that does not ship with bash pre-installed, such as FreeBSD or Windows, you'll need to either use a distribution platform to download and install it, or obtain bash's source code and build the binary yourself. FreeBSD users can use ports, Windows users can use

cygwin, while Windows 10 integrates the Linux Bash Shell natively, but there are alternative distributions. The source code is available from GNU.org. If all else fails, employ the powers of the Internet to find a means of installing bash before you continue.

With bash installed, we can run the binary to start the program. Before we do so, it's important to take note of the two distinct modes of operation that the bash shell supports:

- interactive mode

- In interactive mode, the bash shell waits for your commands before performing them. Each command you pass it is executed. While a command is being executed, you cannot interact with the bash shell. As soon as the command is finished, you can interact with bash again while bash awaits your next command.

- non-interactive mode

- The bash shell can also execute scripts. A script is a pre-written series of commands which bash can execute without needing to ask you what to do next. Scripts are generally saved in files and subsequently used to automate a wide range of tasks.

Apart from the source of the commands bash executes, these two modes of operation are very similar. For now, suffice it to say that if bash is asking you for a command to run, you're in interactive mode. If it's running commands stored in a file, it's running a script in non-interactive mode.

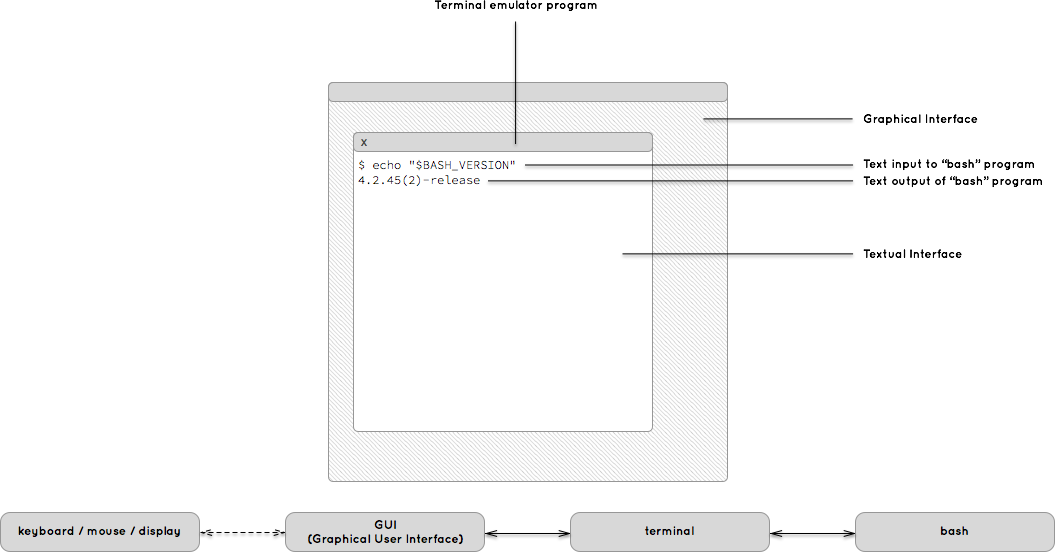

Also recall that the bash program generally runs in a text-based interface. It has no graphical interface for you to interact with, which means that if you're currently in a graphical interface, you'll first need to open a text-based interface before you can perform any meaningful interaction with the bash program. The standard way of opening a text-based interface involves opening a terminal. In the old days, terminals were the hardware devices we used to connect to a computer and interact with it. Nowadays, most terminals are "emulated". That is to say, they are programs on your computer, either graphical or textual, that "emulate" a real terminal in software and create a textual interface for you to use. There is a wide variety of terminal emulators, and the ones available to you vary depending on what system you're on. Linux and *BSD users might use rxvt, xterm, gnome-terminal or konsole. OS X users might use Terminal or iTerm 2. Windows users can use programs such as cmd.exe, Console 2 and mintty. There are many alternatives for each operating system. Find one you like and read on as soon as it's installed and you're ready to start it.

Let's start bash!

First, make sure you're in a text-based interface by opening your terminal or terminal emulator program. Once you're in a text-based interface, you'll need to find a way to run programs. Just like graphical interfaces can vary greatly in how you start programs with them, as can text-based interfaces. Luckily, however, most terminals are configured to start a shell program as soon as it's ready. Remember how bash is a shell program? Chances are, your terminal will start with

bash already running in it. Some terminals, however, won't: some systems may default to shells such as cmd.exe, sh, dash, csh or zsh. None of these shells are bash, and their usage is not covered by this guide (if you need help, I again recommend you turn to the powers of the Internet). To find out whether or not your terminal is currently running a bash shell, let's try running our first bash

command!

$ echo "$BASH_VERSION"

4.2.45(2)-release

If the above command yields no output or results in an error message (assuming you didn't mis-type anything), it means your terminal probably isn't running the bash shell. You'll need to manually start the bash shell before you can try the command again. In most shells, starting bash is as simple as executing the bash command. If not, you'll need to turn to the documentation of your system, terminal or shell, or activate the power of the Internet to find out how to run the bash shell from your terminal.

If you're worried that you don't fully understand how this command works, don't. We'll go in-depth on bash's commands in a later chapter. Until then, you will see simple code every now and then: it'll be mostly obvious and not critical to understand what the code does. For now, take it matter-of-factly. Conveniently, one of the advantages of the bash shell language is that it is fairly easy to understand the simple statements.

What's going on here? Text, terminals, bash, programs, input, output!

Near the end of the last section, you might have noticed we accelerated a bit.

If you're still a bit dizzy from the speed (and otherwise!), let's take a step back and get a clear picture of what's going on. Depending on your level of familiarity with the matter, there may be a lot of new concepts here. Even if these concepts are not new to you, there is a good chance you don't know exactly how to frame them. If you're going to understand what exactly is going on when you run

code on your computer, it's vital that you have a good understanding of how the different concepts interact.

When you start a terminal emulator program from your graphical user interface, you'll see a window open up with text in it. The text that displays in this window is both the output of programs running in the terminal as well as the characters you've sent to those programs using, for instance, your keyboard. The bash program is only one of many programs that can run in a terminal, so it is important to note that bash is not what's making text appear on your screen. The terminal program takes care of that, taking text from bash and placing it in its window for you to see. The terminal may do the same for other programs running in the terminal, completely unrelated to bash, such as a mail program or an IRC client.

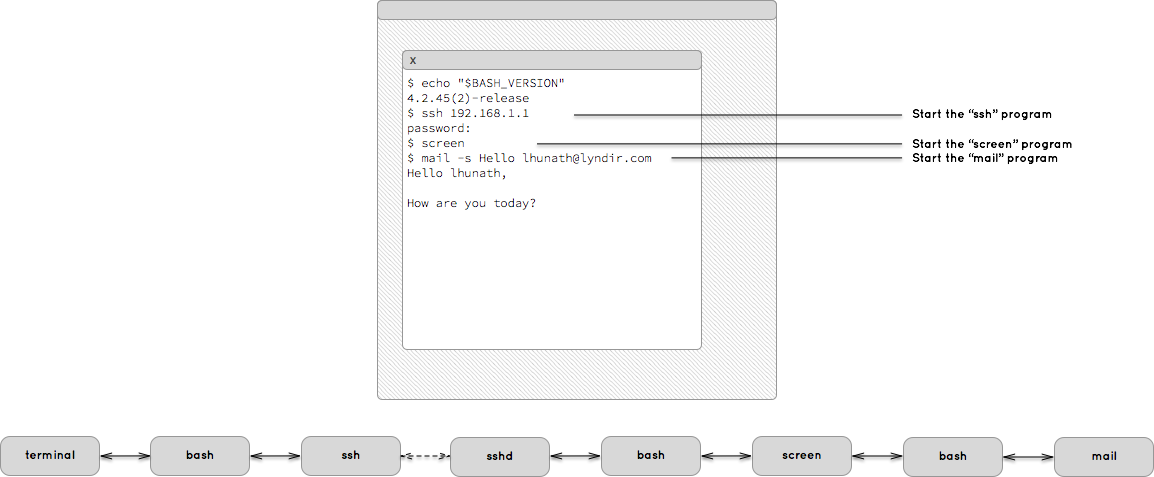

It is sometimes difficult to tell just what programs are currently running in a terminal. In the example above, text from your keyboard goes through a long chain of programs, passed from one to the other, until it reaches its final destination (the mail program running on another computer at IP address 192.168.1.1).

I won't describe these programs in depth, the point here is that terminal programs all inter-connect and work together under the hood. Since there isn't much of a visual reminder about what's happening, it's important that you develop a good understanding of when programs start, communicate and end, so that you can properly understand the effects and side-effects of sending input to or receiving output from various programs in your text based user interface.

Briefly, the above example uses the bash program to run the ssh program, which sets up a connection with another computer. On the other computer, a new bash shell is started, whose input and output are sent back and forth over the connection. We then run the screen program with the remote bash, which is a terminal multiplexer. Such a program is a text-based terminal emulator, which can emulate multiple terminals

using only one terminal display (by using hotkeys to switch between active emulated terminals or displaying multiple of them using split screens). The screen program starts a bash shell to run in one of its own emulated terminals. In this third bash shell, we then run the mail program, which allows us to type in the mail message that we'd like to send.

So what exactly is a program and how does it connect to other programs?

It may seem obvious at first, but upon second thought it's not immediately clear to most what a program really is. Additionally, we're going to try and avoid making claims in this guide that aren't explained, at least within our subject scope, such as the fact that programs "connect" with one another.

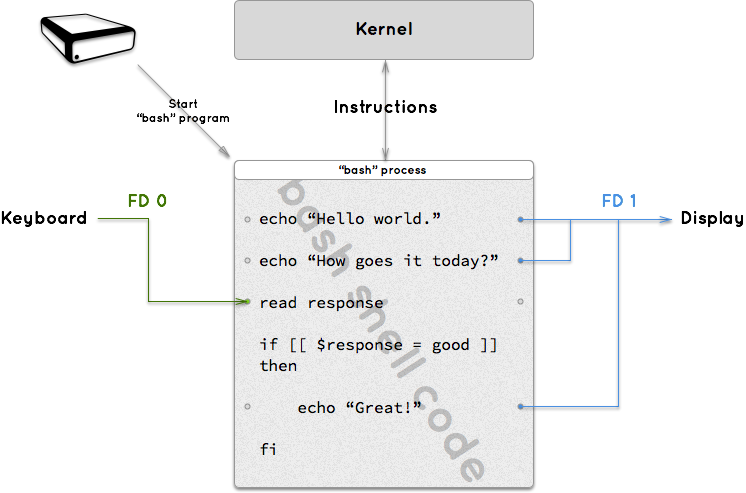

In short, a program is a set of pre-written instructions that can be executed by your system's kernel. A program gives instructions to the kernel directly. The kernel is technically also a program, but one that runs constantly and communicates with your hardware instead.

A program generally lives on your disk, waiting to be started. When you "run" or "execute" a program, your kernel loads its pre-written instructions (its code) by creating a process for your program to work in. As we briefly saw in the previous section, your program can run many times simultaneously, each of those instances are running processes of your program. If a chocolate cake recipe is a program, then your process of baking a chocolate cake with it is the program's process. A process relays the instructions in your program to the kernel. A process also has a few hooks to the outside world via something called file descriptors. These are essentially plugs we use to connect processes to files, devices or other processes. Most chocolate cake recipes won't, but some might have, for instance, a table for looking up the amounts of ingredients based on the desired number of servings. These recipes take input and their output will differ depending on the input given. File descriptors are identified by numbers, though the first three also have standard names:

- standard input

- File descriptor 0 is also called standard input. This is where most processes receive their input from. By default, processes in your terminal will have their standard input "connected" to your keyboard. More specifically, to the input your terminal program receives.

- standard output

- File descriptor 1 is also called standard output. This is where most processes send their output to. By default, processes in your terminal will have their standard output "connected" to your display. More specifically, your terminal program will display this output in its window.

- standard error

- File descriptor 2 is also called standard error. This is where most processes send their error and informational messages to. By default, processes in your terminal will have their standard error "connected" to your display, just like standard output. It's important to understand that standard error is just another plug, just like standard output, which leads to your terminal's display. It isn't dedicated to errors, in fact bash uses it for most of its informational messages as well as your prompt!

A process isn't limited to just these three file descriptors, it can create new ones with their own number and connect them to other files, devices or processes as it sees fit.

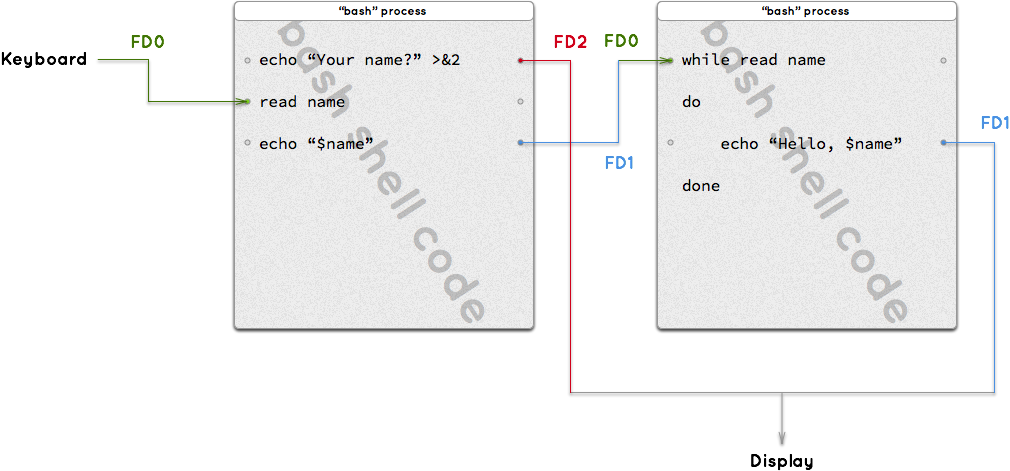

If a program needs its output to go to another program's input, as opposed to your display, it will instruct the kernel to connect its standard output to the other program's standard input. Now all the information it sends to its standard output file descriptor will flow into the other program's standard input file descriptor. These flows of information between files, devices and processes are called streams.

A stream is information (specifically, bytes) flowing through the links between files, devices and processes in a running system. They can transport any kind of bytes, and the receiving end can only consume their bytes in the order they were sent. If I have a program that outputs names connected to another program, the second program can only see the second name after first reading the first name from the stream. When it's done reading the second name, the next thing in the stream is the third name. Once a name is read from the stream, the program can store it somewhere if it may need it again later. Reading a name from the stream consumes those bytes from the stream and the stream advances. The stream cannot be rewound and the name cannot be re-read.

In the above example, two bash processes are linked via a stream. The first bash process reads its input from the keyboard. It sends output on both standard output and standard error. Output on standard error is connected to the terminal display, while output on standard output is connected to the second process. Notice how the first process' FD 1 connects to the second process' FD 0. The second process therefore consumes the first process'

standard output when it reads from its standard input. The second process' standard output in turn is connected to the terminal's display.

To try out this dynamic, you can run the following code in a terminal, where ( and ) symbols create two sub-shells and the | symbol connects the former's FD 1 to the latter's FD 0:

$ ( echo "Your name?" >&2; read name; echo "$name" ) | ( while read name; do echo "Hello, $name"; done )

Your name?

Maarten Billemont

Hello, Maarten Billemont

Notice how the only text that appears in the terminal is the output of the commands that are connected to the terminal's display, as well as the input the terminal has sent to the programs.

It is important to understand that file descriptors are process specific: to speak of "standard output" only makes sense when referring to a specific process. In the example above, you'll notice that the first process' standard input is not the same as the second process' standard input. You'll also notice that the first process' FD 1 (standard output) is connected to the second process' FD 0 (standard input). File descriptors do not describe the streams that connect processes, they only describe the process' plugs where these streams can be connected to.